As in the past few years, the Dutch festival of Sinterklaas has caused some commotion, this year even to an international level when the UN sent in a awfully bad informed committee under direction of Verene Shepherd to check whether it was racist or not.

As in the past few years, the Dutch festival of Sinterklaas has caused some commotion, this year even to an international level when the UN sent in a awfully bad informed committee under direction of Verene Shepherd to check whether it was racist or not.

As a scholar of religion and rituals, I’d like to offer a quick anthropological analysis of at least some of this festival’s rituals.

The festival

The earliest traces of the festival are to be found in the 13th century and are Roman Catholic, which was the only institutionalized church at the time. Quite a few pre-Christian pagan influences that have been adopted be distinguished. Over the time, the festival has evolved to different forms.

The festival is mainly celebrated in the Netherlands, but there are some local variations to be found in Belgium and Germany, encompassing differentiated local traditions.

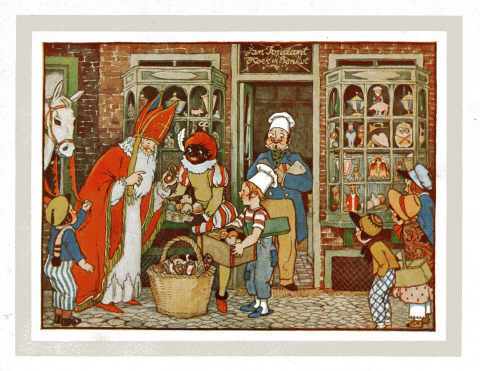

Sinterklaas is the festival of St. Nicholas of Myra. Around this semi-historical there’s a lot of mythology in existence, although little of that is commonly known. This saint is portrayed as a venerable man in a red and gold bishop’s gown. He is known as a friend of children. And principally, the festival is meant for young children to around the age of eight. Revealing Sinterklaas’ non-existence, is a firm taboo.

The young are made to believe that Sinterklaas lives in Spain visits the Netherlands every year in a steam ship, accompanied by his helpers, the dark-skinned Zwarte Pieten ‘Black Petes’, dressed in frivolous colours, to offer presents to all the children that behaved well. Those that have been naughty risk a to be caned by Zwarte Piet, or in extreme cases to be forced in the sack and taken back to Spain.

The period of Sinterklaas arrives at some point in November, which is since television broadcast a national event. Still in many places the arrival is also enacted. From this moment on, the children are entitled to put down their shoes in front of the hearth (or the like) and are required to sing traditional songs. They can offer something of their own making, or food for the Sinterklaas’ horse to appease the saint. The morning after, a small present will be in their shoes. They are made to believe that Sinterklaas rides the roofs at night on his white horse, assisted by the Zwarte Pieten, to spread these presents. The Zwarte Pieten are able to listen and climb through the chimneys.

The climax of the festival is the 5th of December. On this evening the family is central. The children are expected to sing songs from an arsenal, and at some point Zwarte Piet, enacted by a family member, will throw in one or more handfuls of traditional sweets into the room and leave a container full of presents accompanied by rhymes at the threshold.

When children grow older, and are told that Sinterklaas is not actual real, the emphasis shifts from receiving gifts from a supernatural being to sharing with one another. At that point the festival is about gift-giving, usually with the employment of personal rhymes, and creative packing of the gifts, called ‘surprises’.

There are some other occasions in which Sinterklaas en Zwarte Piet are enacted, mostly at primary schools. A visit of Sinterklaas is usually endowed with ritual. They are also widely employed by businesses for promotional purposes.

In the last decades, the Sinterklaas festival has partly been nationalized, since the introduction of the Sinterklaas Journal on national television. The festival has been modernized by including modern popular trends and music. So, there has come to be a national uniform level and the local celebration.

An analysis

Sinterklaas is a calendrical rite on an annual basis. It’s prime moment is Sinterklaas evening, but there is a period of some weeks prior to it that Sinterklaas is already present in the land. Its central figure is St. Nicholas, who is enacted at various occasions. The history and mythology around him are not very significant to celebrants.

The young regard him as an awesome, respectable and holy man who supernatural abilities, which are usually taken for granted. He is the embodiment of good, charity and righteousness.

Sinterklaas’ helper, Zwarte Piet has traditionally been a penalizing figure with a frightful presence, but has changed over the year to a playful, somewhat mischievous character.

After that Sinterklaas’ non-existence is learned of, the emphasis of the festival turns to gift-giving, within a certain ritual context.

The festival employs a wide array of traditional characteristics: The enactment of the characters of Sinterklaas and his white horse, Zwarte Pieten and the steam ship. And a variety of traditional songs, a variety of select sweets, the general lore, rhymes, gift-giving.

To the young ones, the festival can surely be regarded as a ritual of exchange and communion. Small offerings are made by children to appease the superhuman Sinterklaas and in exchange of gifts. At a later age the exchange changes from a quasi sacral exchange to a mundane social level.

A core value is good behaviour, as Sinterklaas – though benevolent – acts as an upright judge. The family is also of great importance; the main celebration of the Sinterklaas takes place at home, when the whole family is present. Also the exchange of gifts, surprises and rhymes are meant to be personal and adding to the family bonding.

The social cohesion is very much served by the festival; for example when all the children of a town are eagerly singing while anticipating the steam ship.

There’s also esoterical symbolism abound, although not very significant to general celebration. For example the relation with the pre-Christian Germanic high god Wodan on his flying horse and raven helpers. Or the Zwarte Pieten, representing the dark night of the soul or the roguish archetype. Or the chimney as the medium between two realms.

The current debate

The figure of Zwarte Piet has in the past few years been the topic of debate, because of skin color in relation to his/their alleged subordinate position to a white man. To an American beholder, his appearance might even be abhorring, because of association with blackface. The discussion has become increasingly complex, due to the classification of racism. There is a growing demand in changing Zwarte Piet’s appearance into all the colors of the rainbow. Personally, I find this somewhat problematic, because the color of Zwarte Piet originates in pre-Christian traditions, and did not originally have a racial element.

On top of that, in the celebration of Sinterklaas this hierarchical relationship does not play a significant role at all. To the celebrants Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet cannot exist without one another. Sinterklaas needs his helpers, and their relation is definitely one of equivalence, even though Zwarte Piet will address Sinterklaas with reverence. Sinterklaas is a holy man, representing the good, and is always addressed with reverence by all, not only Zwarte Piet. And in turn, Zwarte Piet is also to be treated with respect, as he carries the a bundle of twigs (used for thrashing) and the sack (to take one away).

I’ve come to believe that the critique of the past few years derives from an outsider’s perspective, while the Sinterklaas festival means to include all. Behave well, beware of Zwarte Piet and listen closely… was that a horse’s hoof on the roof?

Pingback: Happy Santa Claus Day | ADD . . . and-so-much-more

Pingback: Happy Belated Sinterklaas! December 5 | ADD . . . and-so-much-more